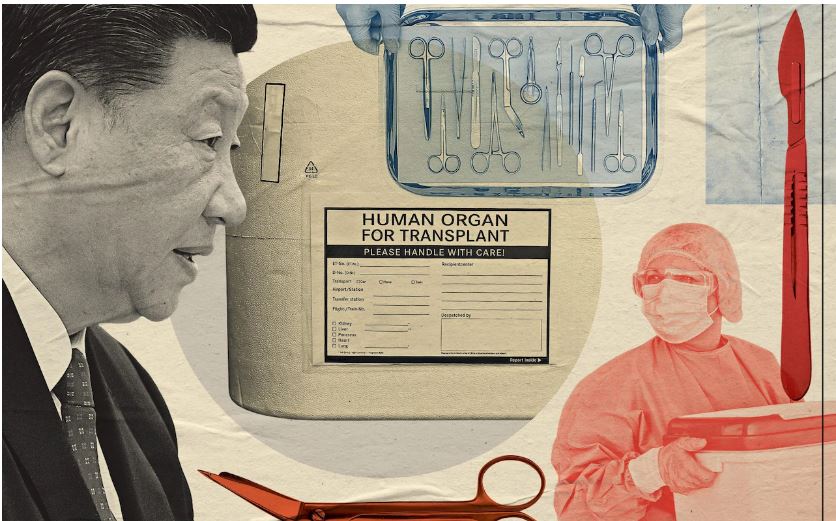

The forced organ harvesting market is lucrative, and some western experts now suspect they unwittingly promoted medics responsible for it

By Henry Bodkin, senior reporter

27 May 2022

Between March 2005 and September 2006 Annie Yang was tortured for up to 20 hours a day in a labour camp outside Beijing for her devotion to Falun Gong spiritualism.

The abuse was relentless. But every few weeks something strange would happen. She and her fellow captives would be herded onto a prison bus with the curtains drawn and driven to a nearby police hospital.

There they underwent a comprehensive series of medical examinations: scans, blood tests, X-rays, you name it. The traumatised women were baffled.

Why was a regime that so wantonly tortured them was also apparently concerned for their underlying health?

It was only when Yang, an antiques trader, fled to the UK after being temporarily released from the camp that the gruesome penny dropped.

“I was shown reports on organ harvesting and realised that was the reason for the scans,” she told The Telegraph. “My whole body was trembling – I could have been one of them.”

Now 59 and working as a freelance translator in London, Yang has no idea how many, if any, of her fellow inmates are still alive.

What has become all but certain in the intervening years, however, is the fact of a state-sponsored system of forced organ transplantation in the country of her birth.

Two years ago Yang gave evidence to an independent tribunal chaired by Sir Geoffrey Nice QC, the former lead prosecutor against Slobodan Milošević, which concluded that Falun Gong practitioners were serving as the principal source for a system of forced organ harvesting in the People’s Republic of China.

Among the plethora of fellow witnesses was Dr Enver Tohti, a former surgeon – now an Uber driver in London – who spoke of being ordered to “cut deep and work fast” by removing the organs of political prisoners while they were still alive.

The findings were largely corroborated a year later by no fewer than eight UN Special Rapporteurs, who described “credible indicators of forced organ harvesting”.

In plain language, victims are killed to order, their bodies sliced open for their livers, hearts, kidneys and lungs, even their corneas. The organs are then sold on a fearsomely lucrative international market. Kidneys go for anywhere between $50,000 and $120,000, and pancreases between $110 and $140.

Experts believe the Chinese Communist Party is also increasingly willing to allow scientific experiments on unconsenting political prisoners, in an echo of the very darkest practices of Nazi concentration camps.

Awareness is – finally, campaigners would say – seeping into the corridors of power in the west. Last month, for example, a government bill was passed banning British citizens from travelling overseas to purchase an organ.

Accompanying this awareness is a growing unease in western academia. Eminent medics are starting to look back uncomfortably on decades of “constructive engagement” with the Chinese medical establishment – those all-expenses-paid trips to lecture budding surgeons, and the profitable arrangements to train batches of them in the west.

Meanwhile editors of academic journals are scouring their back issues for too-good-to-be-true studies on organ transplants, that may have arisen from experimentation on human guinea pigs in places such as Xinjiang.

In October last year a world-renowned Australian transplant doctor, Professor Russell Strong, called on all Chinese surgeons to be banned from western hospitals to prevent them using the skills they pick up there in the organ harvesting market.

Now, a leading human rights body has warned medical equipment manufacturers – among others – that they might be prosecuted if their kit is found to be used in the illegal Chinese trade.

All this implies a disturbing question. Namely, has the west aided and abetted China’s organ harvesting industry?

Or, in more human terms, if Yang had stuck around in Beijing to have her living heart cut out, might that surgeon have received relevant training from a British university, or even the NHS?

‘The punters are desperate’

To understand what drives all this, you need only appreciate the single, simple fact that global demand for organs vastly outstrips legitimate supply.

Professor Martin Elliott, who led the transplant team at London’s Great Ormond Street Hospital for 10 years, puts it bluntly.

“The punters are desperate,” he says. “Remember, if you’re on a waiting list for a transplant, about 25 to 30 per cent will die on that waiting list.

“It’s not surprising that they’re going to be looking around for an organ, and they will grab what they can find. I find it quite hard to blame them.”

The resulting market in organ tourism is thought to be worth up to $1.7 billion a year. One Japanese woman – an extreme case – is reputed to have paid $5 million for a liver.

Transplant “agents” are available in many countries; for a fee they can fix you up with a matched organ in a fraction of the time you would spend on a waiting list.

For a while, health insurance companies in Israel were even offering to help clients find such agents in China.

The incentives, then, are obvious. What is less clear to the casual observer is how in a couple of short decades China managed to become the organ transplant centre of the world.

Wayne Jordash QC is the founder of Global Rights Compliance, a not-for-profit initiative specialising in international humanitarian and criminal law.

He explained China’s rapid progress in a chilling legal advisory note published in April.

“At the beginning of the 2000s the PRC leapt from a follower to a leader of transplantation technology,” it read.

“Despite the absence of a voluntary donation system, the organ transplantation hospitals in the PRC tripled within four years, and transplantation surgery, previously conducted nearly exclusively with kidneys, expanded rapidly to surgeries involving hearts, lungs and livers.”

The volume of kidney transplants grew 510 per cent, liver transplants 1,820 per cent, heart transplants 1,100 per cent and lung transplants 2,450 per cent.

“Simultaneously, transplant tourists and Chinese citizens were reported to have access to a matched organ within weeks or months, in comparison to other countries where patients could be on a transplant waiting list for years despite well-established donation systems,” the note said.

“The transplantations were also able to be planned in advance, with specific dates of organ availability provided to the recipient ahead of time.

“This pre-arrangement stands in stark contrast to a normal organ-matching process between a deceased donor and a recipient that takes place once the donor is determined as deceased and cannot be planned in advance of the death of the donor.”

So, where was this magical supply of organs coming from?

In 2009, Beijing said that two-thirds of organs used for transplantations were taken from death row prisoners, stating that these prisoners granted consent before being executed.

But that simply didn’t stack up. From 2000, the number of executions following a death penalty sentence declined, while the transplantation system grew exponentially.

Among those in the west, suspicion soon fell on the CCP’s ruthless campaign of oppression against followers of Falun Gong, a movement rooted in traditional Buddhist and Daoist teaching that became increasingly popular from the 1990s.

It was banned in 1999, partly, some believe, because the CCP got spooked when the number of practitioners exceeded the party membership.

Mass arrests followed. Since then the number of Falun Gong practitioners who have fallen victim to forced organ harvesting are, conservatively, estimated to amount to hundreds of thousands.

According to Sir Geoffrey Nice’s China Tribunal, 60,000 to 100,000 transplantations took place annually between 2000 and 2014, with Falun Gong practitioners serving as the principal source.

In 2010, China said that from 2015 organ procurement from executed prisoners would end and the system would rely on voluntary donation. But experts don’t believe that for a minute. They point out that the number of organs used in China for transplantations greatly outstrips the number that could ever be garnered from voluntary donation.

The Uyghur Turkic-speaking Muslim minority, who since 2017 have been subject to repression so brutal that both the US Government and UK Parliament describe it as genocide, are feared to be a new source of forced organs.

Only this week, thousands of damning undercover photographs from the heart of Xinjiang’s mass incarceration complex were published, proving the depths of Beijing’s hatred for these benighted people.

It followed evidence presented to the US congress this month of analysis indicating that anywhere between 25,000 and 50,000 detainees of the camps are subjected to organ harvesting and then cremated each year.

Uyghurs are also believed to be the victims of wholesale illegal experimentation.

Professor Elliott, who sat on the panel of the 2020 China Tribunal, said: “The evidence is overwhelming.

“What happens to those people in the camps is brutal and involves extreme torture and the denigration of human life.”

Using force to remove an organ from an unconsenting person, often without anaesthetic, is at the most extreme end of what Professor Elliott terms the “spectrum of evil”. But it is not the only type of coercion. Poverty and desperation are also potent factors in supplying the organ trade, and not just in China.

According to Global Rights Compliance, the average donor is 29 years old and earning an income of around $480 a year, while the typical (male) recipient is 48 years old and earning approximately $53,000 a year.

“The amount of the payment can be considered coercive in the context of the vendor’s financial vulnerability and undermines the principle of voluntary consent that is central to ethical transplantation,” it said.

Or as Wayne Jordash put it with lawyerly understatement: “There is a huge amount of unethical conduct.” Since 2020 this “unethical conduct” has been established, in the view of the tribunal, beyond reasonable doubt.

But for Jordash and his fellow campaigners, the real question now is this: to what extent have we in the west enabled it?

‘You only see this narrow piece of what you are allowed to view’

Professor Elliott is rueful.

“The embarrassing thing was that although I’d spent all my life in transplantation, I was completely unaware of such activities, which is itself an issue,” he said.

“Communication between physicians, within and between countries, has fostered all sorts of research and benefits – I personally have benefited and my field has benefited from them.”

But here comes the rub.

“You are often invited there [China], maybe to give a lecture, maybe to do some teaching, maybe to operate, and you only see this narrow piece of what you are allowed to view.”

It wasn’t just him. In recent decades British medical and academic institutions, warmly encouraged by the government, have been only too eager to share their skills with China.

They have done so under the dictum of “dialogue” – but there’s good money to be made, too.

“It’s important to know many organisations, often with good intentions, make money and obtain benefit from relationships with reciprocal sources in states such as China,” says Professor Elliott.

Take Healthcare UK, a joint initiative between the Department for International Trade, NHS England and the Department of Health, to promote the export of British health services.

Under an arrangement signed in 2013 with the International Health Exchange Centre of China, Britain would make available arguably its four finest medical universities – Oxford, Cambridge, Imperial and UCL – to offer training and assessment for Chinese surgeons.

The agreement also enthusiastically promotes “the UK’s extensive medical equipment supply chain”.

In a sentence which would no doubt chill Yang to the bone, it specifically mentions scanners.

The pact lauded the work of the Royal College of Surgeons of England in China, citing the quality assurance and accreditation programmes that Chinese institutions might like to sign up to.

That 2013 iteration of the deal was withdrawn in May 2019.

However, just last November a joint statement between Sajid Javid, the current health secretary, and his Chinese opposite number agreed to continue to “work together on medical education and training”.

In response to the concerns raised, a government spokesman said simply: “We do not provide training or support for organ transplants in China.

Meanwhile the Royal College of Surgeons England denied accrediting any training in China “that involves organ removal or transplantation”.

However, it was ambiguous in its response as to whether any practical training that could be relevant to transplantation has been offered either in the UK or China.

“This is an issue we take very seriously,” a spokesman said. “The practice of forced harvesting is entirely at odds with the ethical code and our approach to training, which stresses the importance of consent, and good ethical practice.”

Even if no direct transplantation training is or ever was offered – both organisations phrased their responses firmly in the present tense – is any collaboration acceptable with a medical system linked to organ harvesting?

And do such collaborations risk appearing to bestow a western seal of quality on doctors or institutions which may be involved in pure evil?

Professor Elliott said: “The organisations which deal with them [the Chinese] must realise, as we stated at the end of the tribunal, that they are interacting, as far as we were able to decide, with a criminal state.

“Lots of Chinese doctors have come over here, plus the US and Australia. One doesn’t know how it is being applied when they go back.”

Calling in the WHO

What, then, is to be done?

The British Medical Association (BMA) has stuck its neck out and publicly demanded the World Health Organisation (WHO) commission an independent inquiry into China’s organ harvesting.

Dr Julian Sheather, the BMA’s special adviser in ethics and human rights, said: “There is absolutely no doubt that these activities are a travesty of the moral obligations in medicine.”

But note the BMA’s wording: “independent”.

“It’s true to say about the WHO that China is extremely influential in it,” said Dr Sheather.

“My strong sense is that it is a political organisation, and there is a great deal of lobbying and political relationships which mean we would like to see a report by an independent organisation.”

Given the fiasco of its Covid inquiry, does anyone truly expect the WHO to blow the whistle on arguably its most powerful member?

In lieu of any official supranational condemnation, campaigners are hoping the law could act as a deterrent against even unwitting complicity in organ harvesting by western companies and institutions.

The legal doctrine of aiding and abetting is one such possible avenue that could be particularly dangerous for medical device manufacturers. It was used in 1946 to convict the general manager of Tesch & Stabenow, the manufacturer of Zyklon B poison gas, for complicity in the Holocaust.

More recent cases against French and Swedish companies have demonstrated modern prosecutors’ willingness to use it.

Under this scenario, it’s conceivable that the boss of a British manufacturer could find themself in the dock if their equipment was found to be used in illegal organ transplantation. But not, potentially, if they could demonstrate that they had undertaken due diligence before selling it abroad.

And that is the crucial point.

Given the complete lack of transparency in China’s medical system, the state-imposed murkiness of it, could a western firm ever be confident that a diagnostic machine or surgical device would not be put to use for organ harvesting?

“If they cannot satisfy themselves that their equipment is not being used in that way, they need to ask themselves serious questions about whether they should be in that market,” says Sheather.

Perhaps the threat of a PR disaster is at least as big a deterrent as the law, or as Jordash puts it: “The bottom line needs to be hit.”

But both he, Sheather and Elliott are hoping for a broader change of feeling in the west.

“We had this starry idea in the 1990s… that if the west engaged with China, then, a bit like trickle-down economics, somehow China would become a sort of vibrant democratic space,” he says.

“We did the same with Russia and look where we are.”